The Multiwavelength Conversations is a series of interviews where members of the optical and radio communities come together to discuss about the benefits of a multiwavelegth approach in astronomy and what will be the impact of the ORP project. For inaugurating the series, we welcome Prof. Gerry Gilmore, the ORP Scientific Coordinator Opticon, and Prof. Anton Zensus, the ORP Scientific Coordinator RadioNet.

The theme of this series of interviews is "Multiwavelength Conversations", what are the main benefits of a multiwavelength approach to study the Universe?

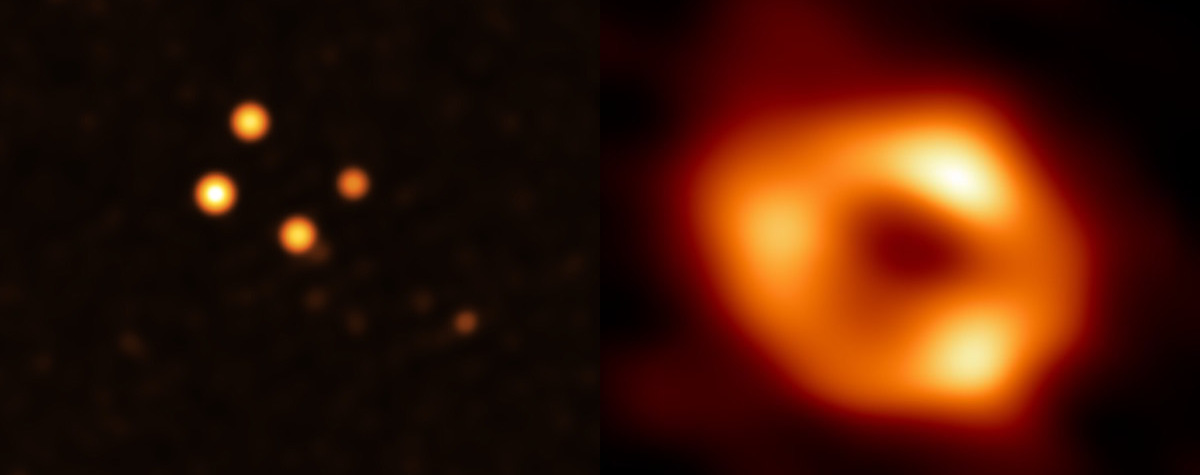

Anton Zensus: From my perspective, the multiwavelength approach is the reality for almost all areas of astrophysics today. My best example is the study of the centre of the galaxy, Sagittarius A*. The supermassive black hole that is sitting there is studied, both from the optical infrared - and that has led to the Nobel Prize winning research and evidence for the existence of a supermassive black hole. And in the radio, we do high-resolution imaging with the ability to hone in much further on the central regions. And, we have been able to create images of that. It's only natural that these previously different communities interact with each other and not only exchange results or discuss these results, but also actually have a common approach in, simultaneous observing sessions that we are now working towards, for example. That's just one example for many of the studies that are being done in the radio and the optical infrared. And then beyond that, high energy and other areas as well. So, the future will have an increasing focus on multi-wavelength and multi-messenger astronomy, including, for example, gravitational waves and other such things.

Gerry Gilmore: Well, that was a beautiful example. And it's particularly apt. The particular example of the focus on the galactic centre is a superb one, because that science is not only Nobel quality, but it has also pushed the technologies to spectacular limits. And so for example, from the optical perspective, it gets all those upgrades and turning the concept of the VLT Interferometer, the VLTI, into a reality. And now with the Wide Field mode for it, it is impacting enormously across huge areas of optical and infrared science. And so, for most of those sources, the ultra high resolution radio capabilities are the natural complement as well. So it is certainly true. There are ways, there are subjects which are single wavelengths domain and say finding planets from radial velocity wobbles was perhaps the highest profile example of that. But the future is broad. And this future is here today. It's not something to dream about. We are a multi wavelength community and we achieve that largely by building a big consortium of people to provide the expertise across the whole range of complex methodologies required. So it's perfectly natural.

We are already one and a half years into the ORP project, what have been your experiences so far of coordinating such an ambitious project?

Gerry Gilmore: Well, the ORP is clearly successful, we got an excellent report from the midterm review, we are achieving the majority of things that we were hoping to have achieved. The big challenge, which is building real, coherent communications across the wavelengths boundaries, is a sociological challenge, not a scientific challenge. The different communities have very different cultures of operating. And even inside the optical part, there are enormous differences between, say the European interferometry initiative, which is a self managing group, and other people who are more anarchic in their approach. As we move into more bigger consortia, broader wavelength ranges, in our future interactions with TNA and the community at large, we have to learn how to manage these challenges and how ORP is providing the opportunity to do this. We don't know the answer yet. Is the best solution, basically, a federal structure in which each subunit looks after itself and just comes together at the top? Or is it more pyramidal? We don't know. But nonetheless, ORP is taking very valuable steps along the way to the future, as well as delivering in the present.

Anton Zensus: My view of this is that the project is indeed ambitious. And it's important to note that of the several pilots that the EC started this period, we are the only pilot that brings two large communities together that have previously run very, very efficiently in their own domains. We, of course, have 20+ years, each of us, in organising, OPTICON and RadioNet, and all those activities there. So, we got off to a running start. We know each other well and I perceive that the initial period, under the leadership of CNRS, has been very constructive. As Gerry says, we'll have to see what is the best way of coordinating efforts into the future. We're doing both - we're still exploring what the common themes and common approaches can be - and will be - and what makes the most sense, as we study the structure of working together. However, the focus for me is also very much on how we partner and continue to partner with the European Union on the co-funding of the so-called transnational access. That's a key point because that's where the focus is for bringing in the larger communities that are neither members nor have access by themselves to these world class facilities that we offer. That, to me is the central point. We've gotten started, as Gerry said, and have had good results so far. I look to the second period for implementation, and then really developing the vision of how the future in this organisational view will be.

Another major action of the ORP project is to continue providing Transnational Access to optical and radio Infrastructures, which was done separately in the past by the OPTICON and RadioNet projects, respectively. What are the benefits and challenges from the new unified funding situation?

Anton Zensus: Central to the transnational access is the funding of these observing opportunities. They are largely carried by the operating institutions of the facilities that we offer in the radio and also optical infrared and these virtual facilities that we bring to the offering for the first time. And the regional centres that we bring to the offering, the virtual facilities were paired, but in particular, regional centres are entirely new things under the transnational access. Therefore, we're both studying new versions of this as a combination. It's challenging to work with half the money. Of course, that is a challenge. However, we want to make sure that we don't lose the large communities that we have built over many years to the benefit of just the smaller one. We need to find ways to continue having a partnership of co-funding between the EC and the operators of the organisations. Obviously, the challenge is to bring these very different communities - Gerry talked about that earlier - that have totally different ways of access, totally different ways of providing the opportunities, historically grown, but also very much depending on the nature of these facilities that we work with. And bringing that together is definitely a task that is not easy.

Gerry Gilmore: One of the interesting challenges of ORP, is that the way that these contracts get set up, the partners are almost exclusively the people who operate the infrastructures, and manage the telescopes, or the data processing centres. And there is nowhere in the EC a system that looks after the users. And so that's the responsibility of projects like ORP, we have to take a broader view and say, we are not just telescope operators who want to ensure our telescopes are used in the best possible way. We also are the only people who can say "well, hang on, there are communities of users out there, and no one is speaking for them". So we have to do that. And, in addition to all the excellent things that Anton has just mentioned, the real value of a programme like ORP is that we can put both perspectives into one place. So instead of having everyone trying to guard the slice of a pie, we can say how can we do the best for everybody?

Anton Zensus: If I can just amplify on that. Gerry is right. A good way to look at this is from the perspective of the users in our community, the RadioNet community, which has been central over the last couple of decades, because we did not just focus on transnational access. Half of what we did in those programmes was transnational access. We had two other elements, two other pillars - the technical development that's needed to evolve and keep these facilities at the scientific forefront. – and also the networking activities that we had that included user support, and in particular the training of the next generation of scientists across Europe and around the world. The task ahead also includes convincing the EC that they too need to continue to have a supporting hand in the future because it's hard to expect the various national facilities to find the required means to look out for a global community. Indeed, that's one of the things that ORP needs to pay attention to and transfer in a positive way into the future, maintaining that community training and engagement and building a European scientific community.

One of the most fundamental challenges that we face nowadays is to preserve the sky for future generations. From light pollution to Radio Interference this is indeed a problem affecting a large portion of the wavelength spectrum used by optical- and radio astronomers. In the past years, this problem has worsened due to the appearance of the satellite megaconstelations. What are the contributions of the ORP project to the protection of dark and quiet skies?

Gerry Gilmore: This is an activity that some of it is coordinated from, from Max Planck in Bonn. It is a project wide activity and by heavy chance, that turned out to be sufficient global awareness that this was an issue, partly because of the continuing threats to radio astronomy that have gone on for years. But also the new threats from constellations of satellites, a plague on both optical and radio astronomy, that an international organisation was set up. And so there is an international approach in which the radio half that is led by the SKA organisation in Manchester, but as a global organisation, the optical paths lead from the US and our activities have fitted naturally into that activity. It was also true and Anton really should be answering this question. But the Max Planck team who are leading on this have actually been European and global leaders in this activity in the radio program for years. And so we were very fortunate that we had the most influential and significant people naturally as part of ORP, and were able to do a little extra to support their work. And that naturally fitted into this global awareness of the bigger issues.

Anton Zensus: Indeed. And in fact, the protection of radio frequencies for the radio astronomers has been a topic for many years. And we had explicit work packages and RadioNet programmes that both did technical development about community awareness- raising activities. The radio frequency allocation worldwide is a very complicated interaction between regulatory bodies, agencies and governance, even as the World Radio Conference where - frequencies that today are very, very valuable assets for industry - are distributed. And whereas originally, there were a number of frequencies protected for radio astronomy, even these very narrow protected bands are being challenged because industry, 5G, for example, the satellite constellations for internet coverage of the globe, and so on, all interfered with the interest of preserving the free frequency space for radio astronomers. So, in ORP, the European CRAF (the Committee on Radio Astronomical Frequencies) is the body that interacts with the Geneva World Radio Conference. And so we can do two things: since we have worked together and now also have the combined strength and effort of the optical infrared protection, we can raise the political awareness of the decision makers substantially. At the same time in that work package, we can also continue to foster the technical developments to be passively protecting our measurements by taking steps to filter out the signals that are interfering with these bands, for example. So, it's both a technical and a political effort that we can jointly undertake in this project.

Talking about the future, the ORP project also continues the tradition of the OPTICON and RadioNet projects about training the next generation of astronomers through Schools and Workshops. What are the plans of the project in terms of combining the expertise of both communities for the training of Early Career Researchers?

Anton Zensus: As you say, both of our communities have had long standing, established means to train newcomers, the next generation, as well as those who come from other communities to use our facilities. What we can do in ORP is to mutually benefit from each other, and individually benefit from the other, by introducing joint training opportunities, for example, and these are still being developed. But there's one example I would like to give, which is the cross lectures that are in development and that will be given at both the NEON and the ERIS schools, which introduce new courses on the protection of the skies, for example, but also on the multi-wavelength aspects of the analysis and learning about techniques and methods and scientific results that have relevance for doing the best possible science in your individual experiment. Therefore, we have a strong focus on continuing with what is working well, but also crossbreeding.

Gerry Gilmore: I agree. I mean, training of the next generation is a critical part of existing schools or a functional part of society, in every part of society. And we've always had lots in all parts of all of our programs. From our perspective, we always tried to put in a broader wavelength awareness, but we were doing it in a sort of secondhand way. So one of the real advantages we have now is that you can get the real experts from each community to come and do that, and share that expertise across the boundaries. So rather than us having to find some time radio astronomer and not really knowing if that was the right person, we now have the elite across the whole community, naturally speaking to each other, and the next generation. And what that means, apart from the fact that we're doing it better, and more of it, is that those people we are training will just simply take it for granted that people across wavelengths talk to each other. And so the psychological impact of that structural change is probably as great as the educational impact

The ORP project also focuses on how to make a more egalitarian, inclusive and diverse astronomical field. What are the main actions of the ORP Project on this topic?

Gerry Gilmore: We have an active program that's coordinated by Francesco Primas from ESO. The key thing to remember is that there's not very much that we can do, because we don't employ staff. So we can, we don't have people whose work packages, work practices, we can interfere and influence. We organise a few meetings, and so we can have meeting codes and so on. But mostly what all we can do is through what you might call soft power. So we can just say these are the sorts of standards that we expect you to follow. And that is the activity Francesca was implementing extremely well, indeed. The other aspect of that program was to say, well, "what is the state of the community? So exactly how much diversity is there at different levels?" And that's really a very hard set of questions to answer. But we are at least able to start to provide consistently collected information across the observational facilities. And we've never even done that before. Everything has been done on an ad-hoc institutional level. So we will at least know the information. Even though we have relatively little direct influence on any individual change. You've got to remember we provide maybe 1% of people's budgets, and no organisation can be changed by such a tiny nudge, but we can set moral examples.

Anton Zensus: It is worth noting that the ORP Board approved the ORP Code of Conduct in November, which, as Gerry said, has been developed in order to maintain the Equality, Diversity and Inclusion aspects on all levels of our activities. Career Development is not something that we can do by hiring diversity, but we can foster the awareness in the activities that we have. And something that shouldn't be underestimated is that in the selection of both, in particular in the training activities that we do, we can pay attention to making sure that the pool of participants is diverse. Furthermore, we can track how they do, how they stay in the field or leave the field if they choose to. This was a good description given by Gerry, I agree with that. We try to be an example - a European example - of how we work together, solution orientated and goal orientated while at the same time maintaining an inclusive atmosphere and approach.

Finally, recently we started the second period of the project, what will be the main focus during this period?

Anton Zensus: From my perspective, implementing the things that we have set up and fulfilling all the ambitions that we have in life and creating results that can be demonstrated as being fruitful and successful outcomes of the projects is one aspect. Many of the things that have been initiated are now underway, others still need some development. So, completing the work programme, if you like, is the reasonable focus. But going beyond that, for me, the main focus is along the lines of what was covered earlier in our conversation. And that is charting the way for the future of cooperation with the EC and the communities, our communities, our institutional facilities, in the best possible support of top-level science in Europe in our fields. Therefore, the activity that Gerry leads - and I'm sure he's going to talk about that - is central. That is also to be the central theme of the task that this pilot - again, the only pilot that combines two communities - is going to make a strong impact on the ongoing Horizon Programmes or future parts of the EU Programmes.

Gerry Gilmore: Well, Anton said that perfectly. But, in any project, it basically comes in three phases. The first part you're doing the preparation work and you're getting ready and ramping up in the middle part, which we're just entering now is when you do the delivering of the new things and make things run smoothly and learn lessons from what you've had before. Start to implement improvements. And then the third part, you focus more on the future. So we're just getting into that. Now for the delivery phase, the technology development stuff, we will have to work out how to roll it out and make it work. So the community will actually see something more than just more of the same.

Gerry Gilmore is Professor of Experimental Philosophy at the Institute of Astronomy, Cambridge University. He established and has led the very successful OPTICON series of EC-funded projects. He is dedicated to a European view of European astronomy, having been involved in UK accession to ESO, in proposing and presenting to ESA, and leading in the UK, the Gaia project, and recently in co-leading the Gaia-ESO Spectroscopic Survey. He is also an enthusiast for time-domain astronomy, and clever exciting new ideas.

Gerry Gilmore is Professor of Experimental Philosophy at the Institute of Astronomy, Cambridge University. He established and has led the very successful OPTICON series of EC-funded projects. He is dedicated to a European view of European astronomy, having been involved in UK accession to ESO, in proposing and presenting to ESA, and leading in the UK, the Gaia project, and recently in co-leading the Gaia-ESO Spectroscopic Survey. He is also an enthusiast for time-domain astronomy, and clever exciting new ideas.

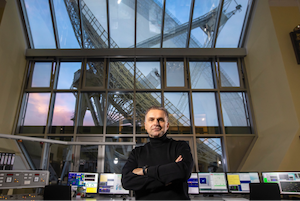

J. Anton Zensus is an astrophysicist and Director at the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy. His research focus lies on finding answers to fundamental questions concerning Active Galactic Nuclei (AGN), using radio astronomical observations. In addition to his research, he has for many years led international scientific collaborations. He served for eight years as the Coordinator of RadioNet and he is the Founding Board Chair of the Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration, which made the first image of a Supermassive Black Hole. Anton is now the head of the European Research Council funded M2FINDERS project, which aims to test the Black Hole hypothesis for AGN and to explain the connection between their powerful radio jets and the central supermassive Black Holes.